We guide families through difficult estate choices with clear, practical information.

In England and Wales, testamentary freedom means you may choose how your estate is shared. That said, the phrase “leaving unequal shares to children in a will uk” summarises the issue many parents face.

Parents often feel a moral duty to reflect past support or present needs. That can mean different amounts rather than equal sums. This is lawful, but it can prompt a claim if someone thinks they lack reasonable financial provision under the 1975 Act.

We explain how to plan, draft clear instructions and reduce the chance of dispute. Simple steps — legal advice, a clear note of reasons and sensible communication — make a real difference.

Key Takeaways

- Testamentary freedom allows personalised choices, but claims are possible under the law.

- Documenting reasons and giving plain information helps executors and reduces friction.

- Professional advice matters most when family relationships are strained or assets are complex.

- Fairness does not always equal equality; past support or current needs may justify differences.

- A brief letter of wishes can explain thinking and ease tensions after death.

Understanding unequal inheritance in the UK and why parents choose it

We often see families divide an estate to reflect real need rather than strict equality. This section explains what those choices look like and why they are made.

What “unequal shares” means in practice

Practically, different splits can be simple. One child might get 60% of the residuary estate while another gets 40%.

Alternatively, one child may receive a fixed lump sum and the remainder goes elsewhere. Both are valid, but clarity matters.

Common reasons for uneven distributions

We see several clear reasons: long-term care provided over years, one child with lower means, or earlier lifetime gifts such as help with housing or school fees.

Recording past support helps show the logic behind decisions and may reduce disputes.

How culture, personal values and family circumstances shape choices

Tradition, religion and close family ties often influence how wealth is shared. Blended families, estrangement or disability also change what feels fair.

Open notes and honest explanation usually mean unequal outcomes are accepted more readily by the family, even when they are hard to hear.

Your legal position in England and Wales: testamentary freedom and its limits

We explain the balance between personal choice and legal safeguards. You have broad freedom over your estate, so you may direct where assets go. That freedom is not absolute.

What you can do with your estate

We can usually name beneficiaries, set fixed gifts or divide the residue as we prefer. These choices let you reflect past support or present need.

Who may challenge under the 1975 Act

The Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 allows certain relatives and dependants to ask the court for more. Eligible people include spouses, cohabitants and children. Such claims often start when expectations were not managed during life.

What “reasonable financial provision” can mean

This phrase is flexible. For adult children it may be modest. For dependent adults the court may award more. Claims raise legal cost and emotional strain, and they can delay estate administration.

- Risk: disputes can damage family ties and slow probate.

- Practical step: clear drafting and records reduce ambiguity.

- Advice: early legal help is usually cheaper than later litigation.

For more on rights after death, see our guide on understand your rights.

Leaving unequal shares to children in a will uk: steps to plan it properly

Start by taking a clear inventory of your assets and debts so planned distributions match reality. List bank accounts, property, pensions, and what falls into the residuary estate.

Map your intended share against the total value. That shows whether fixed sums or percentages work best. Percentages usually suit the residuary estate because they rise and fall with value.

Spot family pressure points and pick strong executors

Make an honest account of family relations. Note past gifts, care provided, or grievances that could spark disputes.

Choose executors who stay neutral and keep clear records. Good executors reduce stress and help your wishes survive scrutiny.

Practical drafting and solicitor advice

- Practical steps: list assets, debts, and joint ownership before drafting.

- Compare: fixed sums suit specific items; percentages suit the residue.

- Get solicitor advice: professionals can reduce ambiguity and assess challenge risk.

Do not delay. Dying without a will leaves intestacy rules to decide, which can undo your plan. For more on practical help see legal advice on unequal distributions.

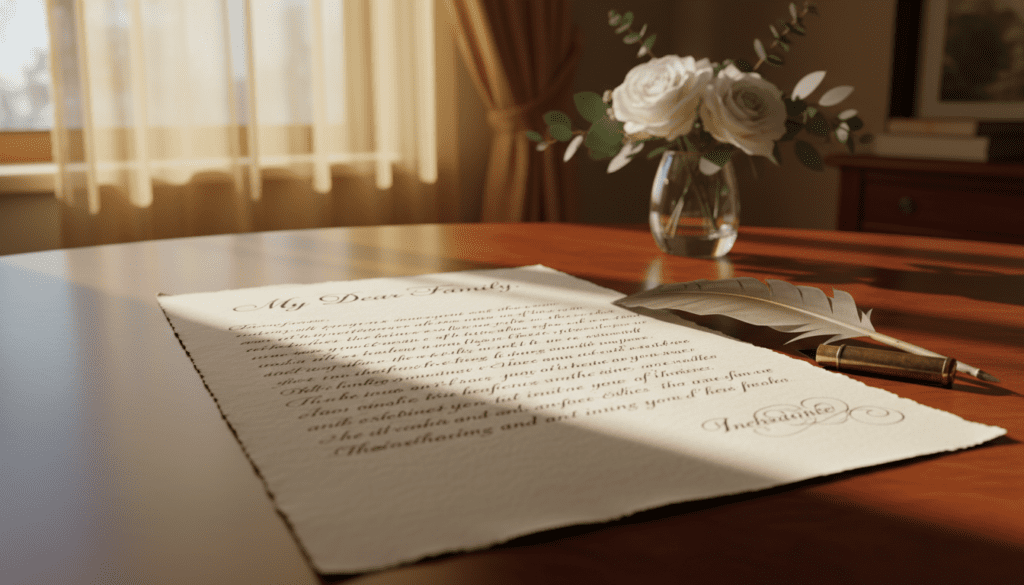

Using a letter of wishes to explain your reasons and protect your intentions

A clear, written explanation of intent gives executors helpful context at an emotional time.

What it is: a letter is a private note that sits alongside your will. It explains the reasons behind choices and gives practical guidance. It cannot change legal gifts, but it helps those who must act.

Legal status and how courts may view it

The letter has no formal legal force under the law. Yet courts and executors often read it when resolving disputes or unclear wording. Clear information may reduce the chance of challenge.

Key elements to include

- A short explanation of your reasons for different provisions.

- A note of past lifetime gifts and relevant dates.

- Practical instructions: who should be consulted, or how sentimental items should be handled.

- Storage details and who knows where the letter is kept.

Tone and common pitfalls

Keep tone calm and factual. Use plain language and avoid blame. That reduces emotional strain and helps readers accept your wishes.

Watch for vague phrases, conflicts with your wills, or failing to update as family circumstances change. Store the letter safely and tell trusted people where it is.

| Purpose | Includes | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Explain motives | Short reasons and dates | Reduces misunderstanding |

| Guide executors | Practical steps and contacts | Speeds administration |

| Record gifts | Past support and context | Strengthens estate narrative |

Drafting the will: making unequal shares clear, workable and probate-ready

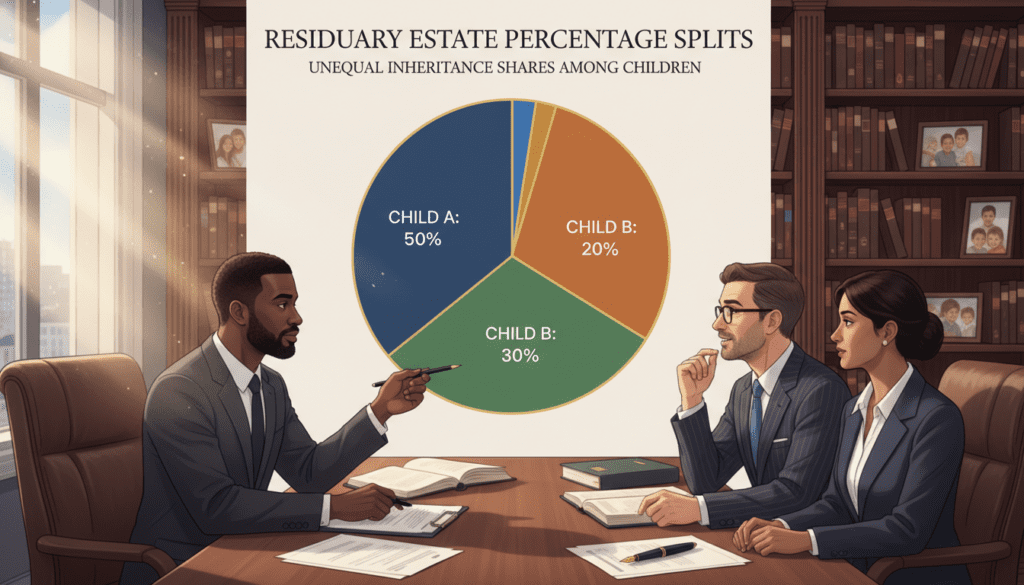

Percentages often give the cleanest solution when you divide the residuary estate. They adjust as asset values move between writing the will and probate.

Residuary estate shares: how percentage splits work in practice

Use clear percentage clauses. For example: “50% of the residue to X, 25% to Y, 25% to Z.”

Alternative beneficiaries if a child dies before you

Name substitutes to avoid unintended gaps. That way, your gift does not fail and executors have plain directions.

Worked example of uneven shares for descendants

Example: everything to spouse first. If spouse has already died, leave 50% to one child and 25% to each of two grandchildren. This is simple and probate-ready.

“Clear, well-ordered wording stops confusion and helps families move on.”

Checking the maths: ensuring totals add up

Before signing, tally percentages so they total 100%. Confirm that fixed sums plus percentages do not overlap.

| Issue | Practical draft | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Percent split | “50% / 25% / 25% of residue” | Automatically adjusts with estate value |

| Alternative | Name substitutes or contingent gifts | Prevents failed gifts at death |

| Probate-ready wording | Clear names, dates and definitions | Saves time for executors and reduces disputes |

For further reading on family expectations and fairness see our practical note on whether each child should get the and guidance on intestacy if you die without a plan at what happens if a husband dies without a.

Managing family expectations and reducing inheritance disputes

A calm chat now can save years of pain and costly disputes later. We recommend weighing the pros and cons before you speak. Timing, privacy and mood matter.

Whether to have the conversation during your lifetime

Talking can help family understand your reasons. It can stop guessing and reduce friction after life ends.

Keep the meeting short and factual. Choose a neutral place and tell people you want to explain values and needs, not to blame.

For guidance on timing, see our note on when to tell your children.

Documenting past support and lifetime gifts without inflaming conflict

Keep an account of any care, loans or help with housing. Note dates, amounts and purpose.

Write the account like a neutral ledger. Facts calm disputes more than opinions.

Use a short letter to explain context. A clear letter of wishes helps executors and family understand motives.

“Silence often breeds assumption; plain records invite understanding.”

| Action | What to record | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Conversation | Who, when, main points | Reduces surprise and resentment |

| Account of gifts | Dates, amounts, reason | Prevents rewriting of history |

| Letter of wishes | Short explanation and storage details | Gives context without changing legal text |

We stress that managing expectation is part of sound planning. Even when feelings run high, simple steps — calm conversation, a neutral account and a clear letter — reduce disputes and protect family ties.

Reviewing and updating your will over time

Small changes now can stop major headaches for those who must act after you die.

We recommend formal checks at sensible intervals and after key life events. Review after marriage, divorce, bereavement, significant changes in finances, or when family relationships shift.

When to review

Consider a full review every few years. Also review after big moves in wealth or care needs. New dependants or grandchildren are reasons to revisit documents.

Keeping the letter aligned

Update your letter whenever you change the legal text. A current letter explains motives and records past gifts. That consistency limits accidental conflicts between documents.

Why regular updates help executors and reduce disputes

Clear, dated records make the job easier for executors. They reduce uncertainty and cut the chance of challenges under the 1975 Act.

| Trigger | Action | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Marriage or divorce | Review and update legal dispositions and letter | Reflects current family structure |

| Major financial change | Rebalance fixed sums and percentages | Prevents unintended shortfalls in the estate |

| New dependants or changed needs | Amend notes and contingency gifts; refresh letter | Shows clear intent for those with need |

| Periodic check (every few years) | Brief review with executor and solicitor | Keeps documents current and defensible |

Practical tip: keep dates on every letter and note who has seen it. For more on rhythms and timing, see our guidance on how often to review your will.

Conclusion

Clear records and kind explanations make it far likelier that your intentions are followed.

Unequal inheritance can be right for many parents. It is lawful, but it works best when your plan is plain and well drafted.

Take stock of your estate. Name reliable executors, use simple percentages or fixed sums and check the totals add up.

A dated letter of wishes that explains your reasons helps calm questions and cuts the risk of disputes.

Keep documents under review as wealth and relationships change. If your situation is complex, get solicitor advice — that step often saves time, cost and family stress.