We explain clearly how the law treats blended families and what that means for your estate planning. In England and Wales, stepchildren are not automatic heirs under intestacy. That means they can receive nothing unless named in a will, even when they are loved and cared for.

We will set out the real-world facts about leaving money to stepchildren vs biological children uk so you can plan with confidence rather than assumptions. We explain the two pressure points: dying without a will, and passing everything to a surviving spouse first.

Blended families often face a higher risk of disputes because the law follows documents and ownership, not family stories. We flag the common gap: stepchildren may be recognised for IHT residence nil-rate band purposes, yet they remain unprotected by intestacy rules unless named.

Our focus is outcomes: who inherits, when they inherit, and what can derail your wishes. For practical guidance on family expectations and planning, see our piece on managing expectations in blended families.

Key Takeaways

- Name people in a will to protect non-automatic heirs.

- The law follows documents and ownership, not family stories.

- Step-relations may help for IHT allowances but lack intestacy rights.

- Wills, trusts and property choices can protect assets and reduce disputes.

- Think about timing: remarriage and joint ownership can alter outcomes.

Why leaving money to stepchildren vs biological children uk needs special planning in blended families

When families combine, simple assumptions about fairness can quickly break down.

We often hear one clear goal: look after a surviving spouse now while keeping later support for children. That goal sounds fair. But it can clash with other priorities.

Common fairness goals and where conflict starts

Typical aims: protect a partner, preserve assets for children, and honour personal wishes. Conflicts usually begin from uncertainty and mismatched expectations. Small gaps in documents cause large disputes.

How testamentary freedom cuts both ways

In England and Wales, you can choose who benefits. That freedom also lets a surviving spouse change things later once they control assets. Remarriage can revoke an old will unless it was made for that marriage.

Remarriage, divorce and later-life relationships

New relationships often change priorities. Divorce, outdated wills and casual assumptions are common triggers for challenges under the Inheritance Act 1975.

| Trigger | Likely outcome | Useful planning tool |

|---|---|---|

| Remarriage | Old will revoked unless specified | New will or marriage clause |

| Surviving spouse forms new family | Assets reallocated informally | Life interest trust |

| Unclear expectations | Disputes and claims | Clear will and letter of wishes |

What the law says in England and Wales about stepchildren, biological children and intestacy

Documents, not feelings, decide who benefits when someone passes away in England and Wales. If you die without a will the intestacy rules apply and non-adopted step relations are not automatic beneficiaries.

What happens if you die without a will

When someone dies intestate the estate follows fixed rules. If the estate value is £322,000 or less, the surviving spouse inherits it all.

If the estate is worth more, the spouse gets £322,000 plus half of the remainder. The other half is shared among the deceased’s children.

How property and the family home pass

Joint tenants pass the whole home automatically to the survivor and that share does not form part of probate. Tenants in common leave their share under a will or intestacy.

When a claim can still be made under the Act 1975

Eligible people may challenge an estate under the Inheritance Act 1975. A long-term, dependent young person or someone promised support may be able to claim.

Check your documents and ownership now. For a practical guide on dying without clear instructions, see what happens if my husband dies without a.

Inheritance tax rules when leaving money to stepchildren

We explain the tax basics so you can see how the estate and the home are treated. Inheritance tax (IHT) normally applies at 40% on values above the nil‑rate band of £325,000. There is an extra residence nil‑rate band (RNRB) of up to £175,000 when a home passes to direct descendants.

Step-relations and the residence nil‑rate band

HMRC treats stepchildren and foster children as direct descendants for RNRB purposes where the link is via marriage or civil partnership.

When the RNRB is reduced

The RNRB starts to taper away once an estate has a total value over £2,000,000. It reduces by £1 for every £2 above that threshold. The relief also fails if the home is not left in a qualifying way.

Transferring unused allowances

Unused nil‑rate band and RNRB can transfer to a surviving spouse or civil partner. That can preserve tax relief for the surviving household and help keep more of the estate for family planning.

Important pitfall for unmarried partners

A partner’s child is not treated as a stepchild for IHT unless the couple are married or in a civil partnership. That difference can change tax outcomes and should shape how you plan ownership and wills.

Practical checklist for your adviser:

- Current estate and property value

- Who will inherit the home and in what form

- Marital or civil partnership status

- Any formal adoption or guardianship details

For deeper practical guidance on rights and protections for family members, see our guide on inheritance rights and protection.

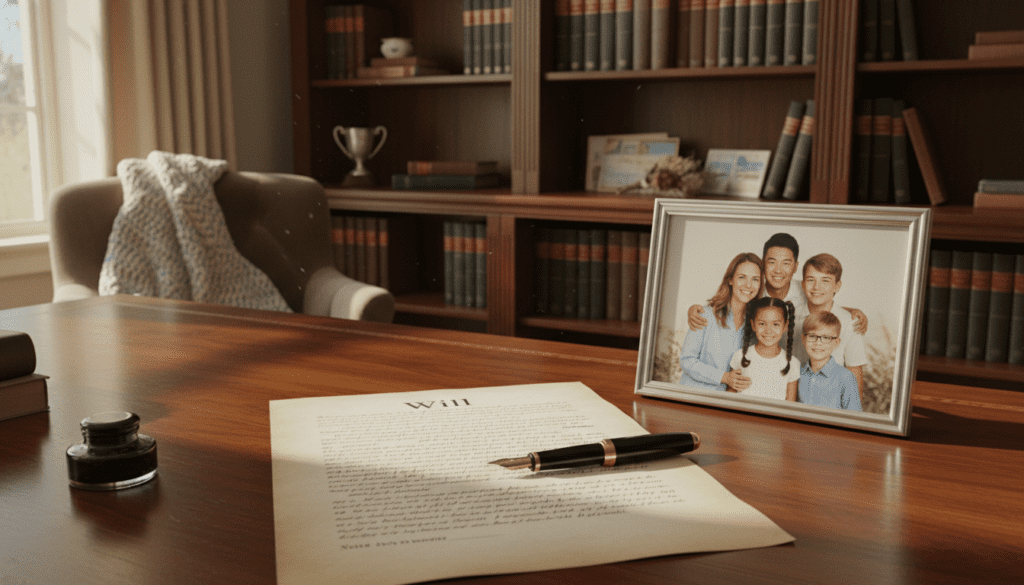

How to write a will that reflects your wishes for stepchildren and biological children

We recommend starting with a clear list of who you mean by “children” and other beneficiaries. Naming each person makes your wishes easier for executors to follow. Short, precise entries reduce delay and stress for the family and the estate.

Naming beneficiaries and handling name changes

Use full legal names, dates of birth and any former names. If someone has changed their name after marriage or by deed poll, note the previous name in the will. That helps probate and links identity quickly.

Keep your will updated after major life events

Review a will every five years and after marriage, divorce, births or deaths. Remarriage can revoke an older will unless it was made in contemplation of that marriage. Regular checks keep your wishes current.

Choosing executors and drafting to avoid disputes

Pick executors and trustees who are organised and calm. Spell out roles and use clear phrases rather than labels like “my family”. A short letter of wishes can explain context without changing legal terms.

| Action | Why it matters | Practical benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Name each beneficiary fully | Prevents identity confusion | Faster probate; fewer queries |

| Record previous names and DOB | Links old documents | Reduces delays |

| Review after marriage or divorce | Legal effect may change | Keeps wishes valid |

| Choose steady executors | Limits family disputes | Smoother administration of the estate |

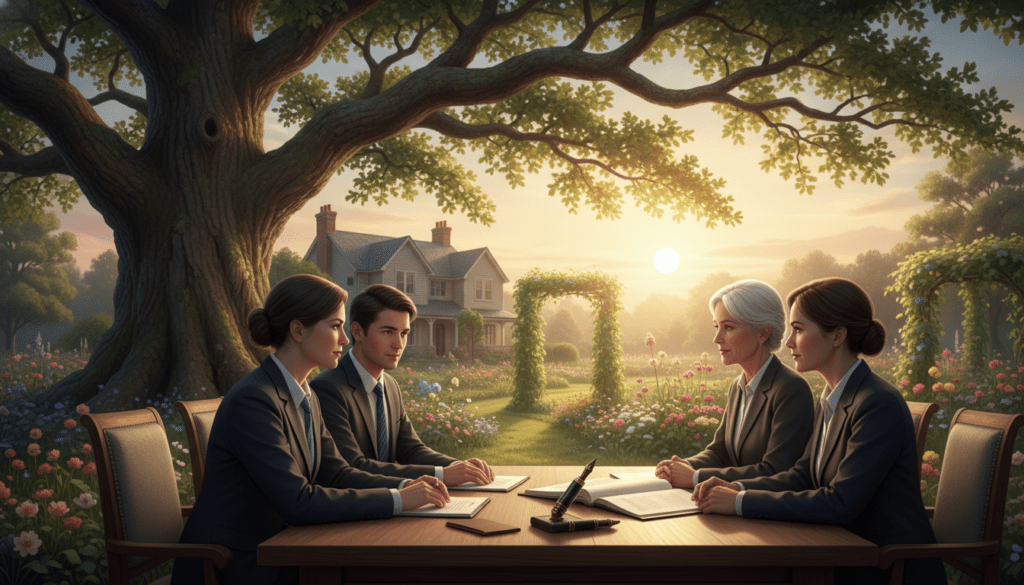

Tools that reduce risk in blended family estate planning

Practical structures stop good intentions from unraveling when someone passes away. We explain simple options that protect outcomes for a spouse and for the next generation.

Why an all-to-one approach is risky

Giving everything to a surviving spouse can hand full control of assets. Later changes in a will, or remarriage, can mean some relatives lose out.

Mirror wills and their hidden risk

Mirror wills feel safe but are not binding on the survivor. A spouse may alter their will, which can alter who the estate benefits.

Life interest trust as a middle way

Life interest trusts let a spouse use the home or receive income while the capital is preserved so children inherit later.

Discretionary trusts and a letter of wishes

Discretionary trusts offer flexibility for changing needs. A short letter of wishes guides trustees without locking in rigid rules.

Property and account ownership

Holding property as tenants in common means your share forms part of your estate and can pass under your will. Joint accounts usually pass automatically, and that can leave little in the estate for any trust to act upon.

- Checklist: confirm ownership of property and accounts; consider a trust; draft a letter of wishes; review documents regularly.

For practical help that aligns plans with family goals, see our guide on protect your family’s future.

Conclusion

Clear documents are the guardrails that stop family hopes from becoming court fights. Estate planning for blended families needs more than good intentions. Name people in a will, check property ownership, and use trusts where suitable.

The legal risk is stark: a step may get nothing under intestacy, so relying on assumptions is not a plan. A practical risk is equally real: jointly held assets can pass outside probate and your will may then have no effect.

Tax rules can help, because step relations can count as direct descendants for some IHT reliefs when the link is by marriage or civil partnership. But allowances and the £2m taper still matter.

Quick checklist for loved ones: review your will; check title (joint tenants vs tenants in common); review accounts; consider a trust. For a deeper look at inheritance rights for step relations see our guide: step inheritance rights.