Facing a dementia diagnosis changes how families think about money, health and home. We explain what shifts and why early planning matters when mental capacity can reduce gradually or suddenly.

This is about protecting independence and wishes, not taking over someone’s life. We introduce clear tools you can use: Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA), an Advance Decision (living will) and an Advance Statement. These help keep the person at the centre of decisions.

We set out simple, practical information to help you plan ahead. You will find conversation tips, a straightforward checklist and a guide to what happens if no documents exist. Our focus is UK law and everyday family life, and we signpost when professional advice is sensible.

Key Takeaways

- Early planning preserves choice and protects health, home and finances.

- LPAs, Advance Decisions and Advance Statements each play a different role.

- Capacity can change over time; acting now keeps the person central.

- We give clear steps, conversation tips and a practical checklist.

- If no documents exist, the Court of Protection may need to appoint a deputy.

What changes after a dementia diagnosis and why planning can’t wait

When someone receives a dementia diagnosis, families quickly face a different set of practical decisions. Small daily choices may stay simple, while bigger questions arrive sooner than people expect.

Capacity can be decision-specific. A person may still choose meals or clothes but struggle with complex finances or medical choices. Mental capacity varies by the task and by the moment.

Capacity can change over time and even day-to-day. Health, stress or the setting can affect how well someone can weigh options. That unpredictability means delaying paperwork can close options later.

We suggest simple ways to keep the person central. Have short conversations in familiar places. Offer two clear options. Write down preferences and small routines that matter.

- More support needs and more paperwork often follow a diagnosis.

- Examples of decisions families face: paying bills, arranging care, managing property and choosing treatment.

- Acting early reduces conflict and keeps the person’s voice present as their ability make some choices changes.

If you want to know what happens without an LPA, we explain the next steps and why putting documents in place is a kindness to everyone involved.

Understanding mental capacity in the UK (and how it’s assessed)

Understanding how someone makes choices helps families act with both care and clarity. In the UK, mental capacity means a person can take in relevant information, weigh up options and communicate a decision.

The core test: understand, weigh up, communicate

The practical test is simple. Can the person understand the information they need? Can they weigh the risks and benefits? Can they tell someone their choice?

Why some decisions are harder than others

Not every decision is the same. Everyday choices like meals or clothes are often straightforward. Bigger decisions, such as selling a home, agreeing to a care package or accepting risky medical treatment, require more thinking and may be harder.

When temporary issues can mimic decline

Short-term problems, like delirium from an infection, dehydration or a side effect of medicines, can affect thinking. These may improve with treatment.

Practical tip: choose a quiet room, avoid busy times and have a familiar supporter present when assessing major decisions. The Mental Capacity Act and the capacity act principles guide these checks, and professionals can help with complex assessments.

Spotting early signs and gathering information before a crisis

Spotting small changes early gives families time to act calmly and protect what matters. Keep an eye on everyday tasks and collect clear information so you can make decisions with confidence.

Everyday red flags: conversations, letters, bills and routines

Unopened post, missed bills and confusion with simple admin are common first signs.

Changes in chat—losing the thread, repeating questions or distress when choosing—also point to trouble. These moments show when a person may need support in making decisions.

Financial warning signs that may indicate vulnerability

Watch for sudden generosity, odd standing orders or strangers pressuring transfers. These are clear examples of financial risk.

Simple protections include call blockers, the Mailing Preference Service and bank alerts for large transactions. Regularly check statements to spot odd activity early.

Keeping a written record to support GP or professional input

Keep dated notes of incidents, with brief facts and times. This information helps a GP or adviser see patterns, especially when symptoms come and go.

Collecting facts calmly saves time and helps people act without panic. That way you can make decision steps with dignity and be ready if urgent action is needed.

| Example sign | What to check | Practical step |

|---|---|---|

| Unopened post | Recent letters and bills | Set up scanned mail or help sort weekly |

| Repeating questions | Conversation changes | Note dates and topics discussed |

| Unexpected transfers | Bank statements | Enable alerts and notify bank if concerned |

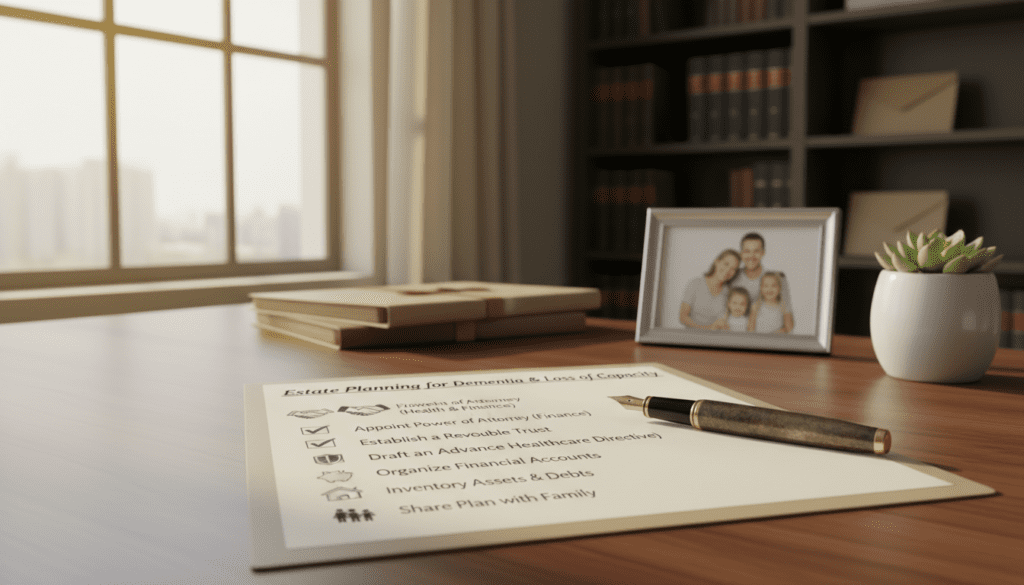

Preparing for loss of capacity due to dementia uk: the step-by-step estate planning checklist

Begin with a simple inventory: what decisions will need prompt attention about health, money and where someone lives?

Key near-term decisions

- Health: treatment preferences, hospital contacts and GP instructions.

- Home: who will manage the property, maintenance and whether moving may be needed.

- Money: paying bills, pension choices, benefit claims and regular payments.

Who to involve

- Family members and close friends who know the person well.

- Carers and care coordinators who handle daily needs.

- Professionals: GP, solicitor, financial adviser and bank contact.

Document timeline

- This month: list decisions, collect account and property details, set up a single folder.

- 6–12 months: register a lasting power or power attorney and record preferences in writing.

- After any health change: review documents, update contacts and re-share copies.

Acting early lets the person choose trusted decision-makers and record wishes. Without this, families often face delay and uncertainty.

| Area | Immediate action | Who to contact |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Note treatment wishes; list GP and hospital | GP, health visitor, solicitor |

| Home | Record property deeds; plan for adaptations or move | Estate agent, builder, family |

| Money | Gather bank details and regular payments; set alerts | Bank, financial adviser, solicitor |

Practical tip: keep scanned copies and give a trusted person easy access. Good organisation reduces stress and helps people act on behalf of the person quickly and with respect.

How to talk about planning ahead with your parent or loved one

Choose a calm time to raise the topic, not a hospital corridor or a rushed appointment. Start with care. Say you want to make sure their wishes guide future decisions.

Lead with respect, not fear. Use short, clear sentences. Listen more than you speak. Let the person set the pace.

Use real-life examples to explain why documents protect independence

Share a simple example: a news story about a scam or a neighbour’s sudden hospital stay. Real stories show how paperwork keeps a person in charge of their life.

Offer one clear choice at a time. That helps the person feel involved and able to make decisions.

Handle disagreement and keep conversations going over time

Expect pushback. People often say, “I’m fine” or “You’re trying to control me.” Slow down. Pause the talk and try again another day.

- Keep chats short and repeat key points.

- Offer simple options and ask which they prefer.

- Remind them this is about protecting independence and wishes.

“We want to make sure your wishes are followed, even if you’re unwell later.”

If you want a clear example of an Advance Decision, see our guide to a living will. Return to the topic over time. Planning ahead is an ongoing conversation, not a one-off meeting.

Put legal decision-makers in place with a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA)

Putting clear legal decision-makers in place gives families confidence and keeps the person’s wishes central. An LPA is a legal document that appoints one or more trusted people to act on behalf of someone if they cannot make certain decisions themselves.

Two different LPAs do different jobs. One covers property and financial affairs. The other covers health and welfare. Many families need both documents to avoid gaps.

Property and financial affairs

A property financial affairs attorney pays bills, deals with banks, manages investments and rents out or sells property when needed.

They also spot and reduce scam risk by setting bank alerts and checking unusual transfers.

Health and welfare

A health welfare attorney can choose care packages, day-to-day routines and where the person lives.

They act on wellbeing choices and speak with health teams about care arrangements.

Life-sustaining treatment

An attorney can only make decisions about life-sustaining treatment if the LPA explicitly gives that power. If not, clinicians take that role.

Choosing an attorney and what changes

Choose someone you trust, who is available and can handle paperwork and difficult decisions. Name backups and write clear preferences to reduce arguments later.

Once capacity is lost, attorneys step in and must act in the person’s best interests, following recorded wishes and keeping good records.

| Area | Property & financial affairs attorney | Health & welfare attorney |

|---|---|---|

| Main tasks | Pay bills, manage bank accounts, sell or maintain property | Arrange care, agree day-to-day routines, decide where the person lives |

| Limits | Cannot make health or treatment decisions | Can only decide life-sustaining treatment if given that power |

| Practical tip | Set bank alerts and list accounts; give clear handling instructions | Record care preferences, daily routines and named carers |

If you want clear guidance on registering an LPA, see our page on lasting power of attorney.

Record treatment wishes with an Advance Decision and an Advance Statement

Writing down treatment choices helps the person’s voice guide care when they cannot speak. These documents make intentions clear and reduce pressure on family and clinicians at difficult times.

Advance Decision (living will): what it can cover and when it is legally binding

An Advance Decision can state which medical treatments a person would refuse in specific circumstances. It can cover life-sustaining treatment and other interventions.

If it is valid and applicable, clinicians must follow it. The document needs clear wording and, sometimes, witness signatures to be binding.

Advance Statement: values, beliefs, routines and preferences

An Advance Statement is not legally binding. It records values, faith, daily routines and what quality of life means to a person.

This helps carers and attorneys understand why a person made certain choices. It reduces guesswork and guides practical decisions about care and daily life.

Sharing documents so they’re used in practice

These papers work best when shared. Give copies to family, attorneys, the GP and care teams. Keep an original in a safe place and scanned copies accessible.

They work alongside an LPA. Attorneys use them to act on the person’s behalf and clinicians consult them when making medical decisions.

We recommend a quick review after hospital stays or major changes. Revisiting wishes keeps information up to date and keeps dignity at the centre of care.

| Document | Main purpose | Who should hold a copy |

|---|---|---|

| Advance Decision | Legally refuse specified medical treatment | GP, named attorney, hospital records |

| Advance Statement | Record values, routines and care preferences | Family, carers, solicitor |

| Combined use | Guide decisions and reduce conflict | All care teams and backup attorneys |

To make sure documents are followed in practice, consider a brief recorded summary in the GP notes and tell key people where originals are kept. If you want help to protect your family’s future, we explain the practical steps and next actions.

How decisions are made when someone lacks capacity: best interests in practice

When choices become hard, a best-interests approach keeps the person’s rights and wishes at the centre. This is a legal and ethical test under the Mental Capacity Act. It aims to protect the person, not to make life easier for others.

Who decides which type of decision?

Everyday choices versus complex financial or welfare decisions

Everyday decisions — washing, dressing, eating or daily activities — can usually be made by whoever is with the person at the time. These do not need formal permission.

Complex matters like bank accounts, property or large financial transactions must be handled by an attorney or a deputy appointed to manage property and financial affairs.

Choices about where someone lives or major care changes are normally made by a health and welfare attorney or deputy, or by professionals when necessary.

Consulting the person, even when they can’t make the final decision

We always consult the person where possible. Short, simple questions and familiar settings help them express views.

Their wishes, past and present, are central to any decision that follows.

Consulting those who know the person best

Professionals must speak to family, friends and carers who know the person well. Their insights about routines, values and past choices guide what is in the person best interests.

Best interests meetings for complex choices

For difficult decisions — often about a move to a care home — teams hold a best interests meeting. Attendees include clinicians, attorneys, carers and family.

These meetings aim to weigh risks, benefits and the person’s preferences and then agree a clear plan that is honestly about the person’s interests.

When an IMCA may be appointed

An Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) steps in when there is no suitable family or friend to consult, or when serious disagreement exists. An IMCA speaks on the person’s behalf and helps keep decisions focused on their welfare.

Practical note: even without perfect paperwork, the Mental Capacity Act requires a respectful, person-centred process. When you need clear, practical guidance on the law and advocacy, see our summary of the Mental Capacity Act and advocacy.

If there’s no LPA in place: deputyship and the Court of Protection

When no attorney is appointed, families often find decisions shift to doctors and social teams. That can be unsettling when a person can no longer make certain choices themselves.

Health and welfare

When professionals may make health and welfare decisions

If an LPA is not in place, healthcare teams and social workers may make immediate health and welfare decisions. They must consider the person’s values, beliefs and past wishes.

Property and money

Applying to become a deputy to manage property and financial affairs

To manage property or bank accounts you can apply to the Court of Protection to become a deputy. Deputyship lets a named person deal with property and financial affairs, but the process can be slow and costly.

| Urgent situation | Why deputyship may be needed | Example action |

|---|---|---|

| Paying care fees | Access to bank accounts | Apply to Court of Protection |

| Protecting a home | Property must be secured or rented | Arrange emergency repairs or tenancy |

| Large transactions | Banks block activity without authority | Provide court order or documented consent |

Why acting early avoids delay, cost and uncertainty

Acting sooner is usually cheaper and faster. An LPA prevents the need for deputyship and reduces family stress.

If you must seek deputyship, gather ID, bank details and records of the person’s wishes. Take legal advice and prioritise urgent decisions while the court process runs.

Conclusion

A calm, short plan now saves time and stress when decisions become hard.

Early action helps the person keep control. Registering a lasting power or power attorney gives clear legal authority to act on a person’s behalf. That avoids slow, costly court routes later.

Remember: mental capacity varies by task. Support and simple choices can help someone make decisions for longer than you might expect.

Ask an attorney to follow the person’s values and record health and care wishes in writing. This keeps actions honest, respectful and practical.

Choose one small step this week — gather key papers, book a GP chat, or start a short conversation. We’re here to guide the next move.